We’ve spent our fair share of time in the mountains, personally and professionally, and one of the largest obstacles we face is not the terrain but the altitude. As the elevation increases, our bodies undergo significant changes and we’ve seen even the fittest people humbled by the thinner atmosphere.

Acclimatization is the process of allowing the body to adjust gradually to high-altitude environments. Rushing the ascent or ignoring symptoms of altitude sickness can lead to serious complications, which is why understanding and respecting this process is crucial.

Seriously, we cannot stress enough how important it is to listen to our bodies and to take the altitude into consideration.

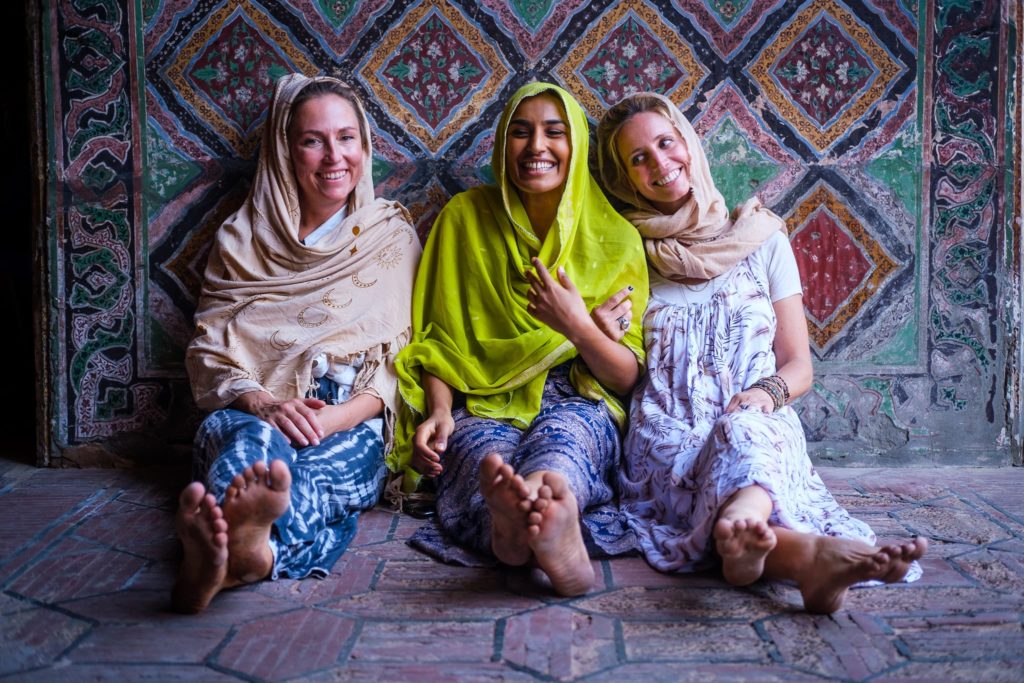

In this article, we’ll break down what happens to the body at altitude, how to acclimate effectively, and what to do if things go wrong. Whether you’re trekking in the Karakoram or Nepal, exploring the Andes, or tackling another high-altitude expedition, following proper acclimatization strategies will help ensure a safer and more enjoyable experience.

What happens to our bodies at higher altitudes?

There’s a common misconception that there is less oxygen at higher altitudes, which is why we have trouble breathing; this is not necessarily true. What actually happens is that, as we ascend, air pressure drops and consequently oxygen becomes less available to us to absorb.

When ascending to higher altitudes, the body encounters lower atmospheric pressure, which reduces the amount of oxygen available for each breath. While oxygen remains at 21% of the air composition, the decrease in pressure means fewer oxygen molecules reach the lungs. This can lead to hypoxia, a condition where the body’s tissues do not receive adequate oxygen, affecting overall function.

To compensate, the body initiates several physiological responses. Breathing rate increases to take in more oxygen, and heart rate rises to circulate oxygenated blood more efficiently. Over time, a more significant adaptation occurs in the blood itself. The kidneys release erythropoietin (EPO), a hormone that stimulates red blood cell production. More red blood cells enhance the oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood, improving oxygen delivery to muscles and organs. Additionally, hemoglobin levels increase, further optimizing oxygen transport.

As the body starts to produce more red blood cells though, the blood also thickens. Thicker blood puts strain on the cardiovascular system, requiring more effort to circulate, which in turn increases the risk of AMS. Ultimately, as the body adjusts it will be more prone to complications but will eventually adapt and reach a new homeostasis. (Interestingly, people who live at higher altitudes, such as sherpa, actually have thinner blood to account for this physical reaction and so are less likely to suffer from altitude-related illnesses.)

What does it mean to acclimatize to altitude?

Acclimatization or acclimating means allowing your body to get used to higher altitudes. This often entails traveling at a certain pace and sleeping at certain points along your journey, giving your body the time it needs.

Arriving directly at a location, say by plane, that is significantly higher than where you departed from is not allowing it to acclimate. A good example is flying into La Paz, Bolivia: at 3700 meters high, La Paz is one of the highest major cities in the world and people often travel there from significantly lower altitudes. Their bodies react poorly when they arrive because they are suddenly exposed to the new environment.

Climbing too quickly and sleeping much higher than where you camped before is also not a good way to acclimate. Beyond a certain point, we need to take our time and let our bodies adapt to the new, hypoxic environments. Otherwise, like the previous example, complications arise.

So to recap, acclimatizing means being aware of our environment and how we react to it. We don’t want to take on too much too quickly and, like exposure therapy, we condition our bodies to perform better by slowly exposing them to certain elements, in this case, altitude. That might mean visiting somewhere slightly lower, like Sucre before La Paz, arriving early, before a trip starts to give yourself time to just chill out at altitude, or adding an extra day to our trekking itinerary to space it out.

How long does it take to acclimatize to altitude?

Unfortunately, there’s no sure answer to this question – everyone acclimatizes at their own pace. Some might experience symptoms relatively early on and struggle to get ahead of them while others might never feel a problem at all.

It’s important to have patience when it comes to acclimatization. Your body will adjust at its own rate and will take as much time as it needs. It may not acclimate as fast as you like, but you don’t have a ton of say in the situation. If you’re taking part in a multi-week expedition, like K2 Base Camp, expect to be acclimating the entire time.

Of course, there are ways to make the process more comfortable and you can potentially start acclimating before a trip even starts. We’re going to get into that next.

How to acclimate before the trip starts

It is actually possible to start your acclimatization before you even arrive at your destination. Pre-acclimating may not be quite as effective, but it certainly doesn’t hurt.

Here is what you can do to acclimate both leading up to and immediately before your trip starts:

- Acclimate in a different location: A lot of mountain climbers, especially those tackling multiple 8000ers, will take advantage of their previous exposure to altitude and actually retain some of their acclimatization. If exposed to significant altitude for a significant amount of time (at least two weeks), people will actually remain acclimated for several months after. So if you have room in your schedule, taking a smaller trip before your larger one can still help you prepare.

- Try to get enough sleep: Rest is another big one. It is not, however, always super easy to sleep through the night without a few wake-ups if you are both jet-lagged AND trying to sleep at high altitude suddenly. We recommend taking a non-narcotic sleep aid; a mixture of Benadryl (an antihistamine) and melatonin your first few nights to achieve the “knock out” effect where you can bank a solid 8-10 hours of delicious, uninterrupted sleep.

- Don’t party: A lot of people like to go out on the town and tie one off before the start of the trip; this is especially common in places like Kathmandu. Stay off the booze until after your expedition is finished as getting drunk is not a good way to kick things off. It is actually pretty normal to feel a bit hungover during your first few days at altitude so don’t contribute to that feeling by attempting to outdrink the locals.

- Go for acclimatization excursions: take day trips to higher places and get that acclimation started. Examples include visiting Chacaltaya (5400m) during our Bolivia expedition or Deosai (4400m) before K2 Base Camp. This go high sleep low approach is tried and true at helping the body acclimatize.

- Start a cycle of medication: dexamethasone and acetazolamide (Diamox) are both common medications prescribed to help combat altitude sickness. Contrary to common practice, it’s more effective to start taking these prior to entering high altitude zones, not during. It’s also important to remember that not everyone reacts well to these drugs. Always consult a medical professional before taking any sort of medication.

Altitude and Hiking Fitness

People who are generally fit and consider themselves strong climbers or hikers may believe they will adjust to high altitudes better than those who are less fit.

This isn’t always the case! While being fit does help in the mountains in general, it doesn’t determine how your body will respond to lower oxygen levels.

Physical fitness doesn’t guarantee better acclimatization to high altitudes. Acclimatization is more about how the body adjusts to reduced oxygen, involving processes like increased red blood cell production and more efficient use of oxygen. While fit individuals may handle physical strain better, this doesn’t mean they will acclimate more quickly or be less susceptible to altitude sickness.

Factors like the pace of ascent, genetics, previous high-altitude experience, and maintaining hydration and nutrition are more important for proper acclimatization. So, no matter your fitness level, all climbers need to follow acclimatization practices like gradual ascent and watching for signs of altitude sickness.

The takeaway: hyper-fit gym enthusiasts, leave your ego behind—otherwise, the mountains will quickly remind you of your limits.

How to continue acclimating during the trip

Once your trek has actually started, it’s usually just a matter of taking things gradually and staying aware of yourself. Take it slow and follow the tips below to reduce the chances of you suffering any altitude-related problems.

- Stay hydrated: simply drinking enough fluids will go a long way in generally making you feel better at high altitudes. Your body will be voiding a lot of liquid (urinating) as you climb higher – a consequence of the kidneys working harder to avoid alkalosis – and you will need to replenish these fluids more often than you’re probably used to. Staying hydrated will help your body run more efficiently as it works harder to adjust to the new environment.

- Take it easy: Don’t push yourself too hard and don’t try to be the fastest in the group. Once you’re exhausted it’s much more difficult to recover at higher altitudes. This is a marathon, not a sprint, and if you use up everything you have in the first few days of the trip, you’re not going to have anything left for the end.

- Prioritize rest: let’s reiterate that saving your strength and energy is HUGE in the mountains. Altitude destroys your sleep cycles as your body is not getting oxygen at the same rate it was before and it is very common to wake up in the middle of the night gasping for breath. Sleep deprivation* can often feel like altitude sickness and sometimes exasperates it. Camp is for RESTING, so take a load off when you get there.

- Don’t climb too quickly: beyond 3500m, you shouldn’t be sleeping more than 300 meters higher than where you were before. Although some people push the envelope a bit, 300-500 m is the industry standard and has proven to be the most effective threshold.

- Keep an eye on yourself: It’s crucial to pay attention to your body for any changes, discomfort, and overall well-being while spending time at high altitude. If you suspect you may be developing a more severe form of altitude sickness, the best course of action is to descend as much as possible. Never keep ascending if you’re feeling significantly unwell.

- Protect yourself from the sun: The UV rays from the sun are stronger at higher altitudes and can exacerbate mild AMS symptoms if you do not protect yourself properly. Use plenty of suncream throughout the day, cover your head, use a buff, and consider wearing long sleeve shirts, even on hot days.

* Sleep medication is a bit of a contentious issue in the mountain climbing community. Many try to avoid it because it could cause complications; many more climbers can’t manage without them and take something anyway. Consult a medical professional about the risks of taking narcotic sleep aids at higher altitudes and weigh the options yourself.

When acclimatization fails

Sometimes, the body never really gets used to its new high-altitude environment. Maybe it’s the circumstances, maybe it’s physical pre-dispositions, maybe it’s something else. Regardless, if altitude-related complications start to arise, trekkers need to be ready for them.

Acute Mountain Sickness (AMS) is the most common and mildest form of altitude sickness. Symptoms include headache, nausea, dizziness, fatigue, shortness of breath, loss of appetite, and difficulty sleeping.

We see mild forms of AMS on a regular basis on our higher-altitude trips, and frankly, it is realistic to expect some version of it at some point. In such cases, we will usually slow things down and monitor the situation. Ultimately, mild AMS doesn’t mean it’s time to call it quits; it just means we need to start being extra cautious of the situation and observing how things develop.

AMS is not HAPE or HACE (both of which we discuss next) and if you start suffering from things like headaches, insomnia, or being out of breath, it doesn’t necessarily mean you’re in the worst situation possible. Things can certainly progress, but level heads usually win.

That being said, AMS is certainly not fun to deal with. It can be very uncomfortable trekking sleep-deprived, struggling to breathe, and not knowing what’s going on internally with your body. In such cases, it pays to find support in your team and guides. They’ll help you along the way, monitor your progress, and often have a better idea of what needs to happen next.

Serious altitude sicknesses

The following more serious forms of altitude sickness are very rare and typically experienced by people at extremely high altitudes above 7000-8000 meters.

High-Altitude Cerebral Edema (HACE): A severe and potentially life-threatening condition where the brain swells due to the effects of high altitude. Symptoms include severe headache, loss of coordination (ataxia), confusion, hallucinations, and unconsciousness. It can develop from AMS if not treated promptly and often resembles hypothermia. If someone is acting “drunk” without drinking, their brain functions are most likely obstructed and HACE is a possibility.

High-Altitude Pulmonary Edema (HAPE): Another severe condition where fluid accumulates in the lungs, making breathing difficult. Symptoms include shortness of breath even at rest, extreme fatigue, a feeling of suffocation at night, cough producing frothy or bloody sputum, and chest congestion. HAPE often sounds like pneumonia i.e. rattling in the chest when breathing.

It can be difficult to diagnose either of these ailments, especially self-diagnose. The symptoms are often confused with those from other illnesses and people either over-diagnose or ignore the signs altogether.

Be sure to listen to your guides and fellow trekking partners when you’re in a high-altitude situation. They will often notice something’s off before you do, either because your cognitive capabilities are too compromised or they know better.

What to do when suffering from altitude-related problems

If someone is suffering a concerning amount from the altitude and is starting to deteriorate, there are a few options; none of which includes continuing up:

- STOP and wait: staying put and waiting for someone’s condition to stabilize is often the first line of defense; sometimes, rest is all they need. Case and point, many people will arrive at Concordia feeling very out of sorts and will opt out of the hike to K2 Base Camp the next day, preferring to remain behind. A few days of rest at a consistent altitude will often do wonders for their health, and by the time the rest of the group returns, they’ll be ready to tackle the much more difficult Gondogoro La.

- Start losing altitude: if someone is still suffering from altitude-related symptoms after not climbing for a day or two, it’s time to start back-tracking. Losing altitude is the only known guaranteed way to curb altitude sickness and is sometimes the only option. While going backward might not be one’s preferred choice, mountaineers actually do it all the time on their climbs as it’s effective. If you start feeling better down lower and there’s still enough time in your itinerary, you can still go back up again.

- Call an emergency evac: should the worst come to worst and someone is unable to take care of themselves, either because they’re physically incapable or there’s some obstruction, then the last resort is an emergency evacuation. Ideally, this will come in the form of a helicopter but this might not always be possible. Helicopters require pristine weather conditions to fly and flat ground to land; neither of these is assured in the mountains. A forced march with a team and pack animals may be all that’s available.

Should the worst-case scenario occur, you’ll want to make sure that you have the proper staff on hand and good insurance. Evacuations are not cheap and there’s often a lot of red tape involved; should you get stuck with a bill, it’ll be an insult on top of injury.

We’ve handle a couple e of evacuations over the years and know how to properly organize one. For that matter, we’ve also dealt with insurance companies a lot as well and know which ones to trust. We broke down the best trekking travel insurance to have in another blog article and highly recommend that everyone check it out.

Wrap Up: How to Acclimatize Properly

Altitude is not something to take lightly, and as we’ve outlined, acclimating to it requires patience, awareness, and preparation. The mountains are humbling, and no matter how fit or experienced someone is, altitude can affect anyone. The key to a safe and enjoyable high-altitude adventure lies in respecting your body’s limits, allowing it time to adjust, and being mindful of the signs of altitude sickness.

By following a gradual ascent, staying hydrated, prioritizing rest, and preparing beforehand with acclimatization hikes or medication, you’ll give yourself the best chance of adapting well. And if things don’t go according to plan, listening to your body, trusting your guides, and being willing to descend if necessary can make all the difference.

At the end of the day, the goal isn’t just to reach the summit—it’s to enjoy the journey and return safely. By acclimatizing properly, you’ll not only improve your chances of success but also make the experience far more enjoyable. So take your time, trust the process, and embrace the mountains for the challenge they are. Happy trekking!