*The following story is a guest post by Snow Lake 2022 team member, athlete, author, and photographer – the one-and-only – Josh Lynott. Photos by Josh Lynott and Jackson Groves*

Perfection isn’t a place, nor is it an object. It is not something that shimmers under the sun or a piece of craft refined to the last degree. Perfection is a comical irony: We put it on a throne in an imperfect world, an unattainable crown we wish to wear. Perhaps, perfection is a collection of happenings and circumstances that fall in alignment.

Should we find, feel, or see this alignment — we should cherish it just as we would upon sighting a shooting star burn out across the night sky.

If we only recognize perfection because we place it against the world’s ugliness, then alignment in a world of busyness and chaos must be recognized as perfection too. Besides, the most famous pieces of art are not memorable for how straight the brushstrokes were.

The best of life and art is messy and contradictory, just like an adventure in the Karakoram. I would not notice the perfect snowflake if it fell into the expanses of white snow. Instead, I saw it because it fell inside my tea-stained mug. Perfection is only recognized when it has a place to land that is not its own.

I spent the last three weeks on an expedition in the wilderness of the Karakoram. Simply put, the Karakoram is demanding, unrelenting, and harsh. Yet, against the odds, I was part of the perfect adventure. My great friends Jackson and Chris teamed up to host and lead an expedition to a place neither of them had ever been.

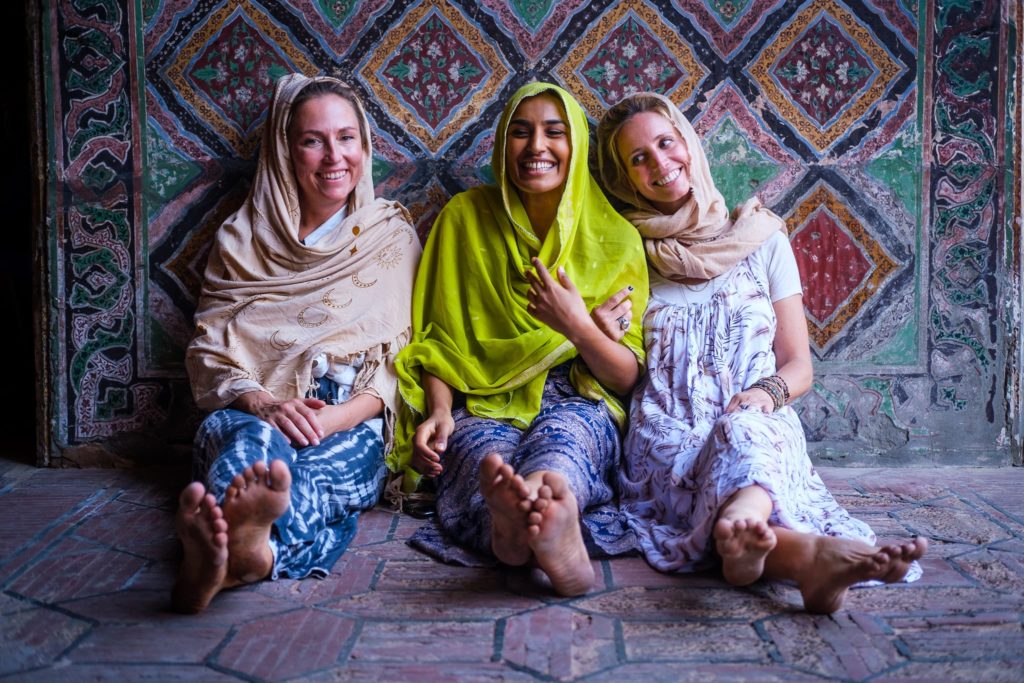

Jackson advertised the trip, and Chris looked after logistics. Together they pulled together 10 clients to lead out into the depths of Pakistan’s glacial highways. A team assembled from all corners of the world. Each of us had little idea of what we were in for. There was no shortage of enthusiasm. Adventures of this nature typically attract a specific archetype. All members’ characteristics included curiosity, a good sense of humor, the ability to endure, unwavering positivity, humility, and a desire to explore the unknown.

Gear in order and weather on our side, we landed in Skardu. A 45-minute flight from Islamabad instead of a 24-hour drive on one of Pakistan’s most dangerous roads. Small wins hold dear to the thought that their butterfly effect will make significant impacts. Sure enough, landing a simple flight meant we didn’t have to use up one of our precious ‘buffer days’.

Skardu is the gateway to the mountains, the land of spare mountaineering equipment and constant power outages. We purchased a couple of new decks of cards, refined our duffels, and piled them into the jeeps. We worked our way through flat tires, shakey roads, and tired drivers (who just needed a puff of a cigarette). We became acquainted with our tents and tent-mates and were ready to embark on our mission to make a pass of Snow Lake.

None of us knew what Snow Lake looked like, where it was, or how we planned to tackle it. Trekking is simple, wake up at ‘Point A’ and go to bed at ‘Point B’. Put one foot in front of the other, try not to fall over too many times, eat your boiled eggs, and ensure you have someone in sight, so you don’t get lost. We had a few porters that had made it across the pass in previous years and a guide ready to lead an army. (I’m not kidding, 13 crew and 40 porters constitute a small army.)

The goat man strolled along, grunting at his goat, the Karakoram sun hit hard, and the first glacier found itself under our feet. Sunscreen was optional. It should have been mandatory. Our first and only place to bathe was presented, and some of us jumped at the opportunity to refresh in the glacier’s pool of refreshment.

The rest of us would simmer in the sun (especially our Canadian counterpart) and go on for two weeks without a shower. It doesn’t take long for the Karakoram to start wearing you down. Heat stroke and gut issues were making friends quickly with the team. Both are valid reasons to be upset, but it was noticeable from early on that our team wasn’t familiar with the act of complaining.

Stretching sessions, mess tent naps, and biscuits ensued. If you want to keep trekkers happy, give them snacks and a mat to lay down on. Chapatis followed, as did a batch of delectable mangoes. Get some sleep, and I’ll see you at the toilet tent in the morning. On my first visit to the toilet tent the following day, I decided I would be doing my business out in the wild from that point onwards.

We were back onto the glacier for another day of ankle-testing conditions and mind-bending-rock-walking. They say if you want to go far, go together. This is true, but if you want to go anywhere, you better go slow. Progress was steady, and at the first opportunity to leave the ‘rock runway’, we did. Down onto the glacier (off the rock section), the world below our feet was a kinder place. For those that wanted to move faster, they did. We agreed that everyone could ‘hike their own hike’ if they had someone in sight or a porter nearby.

I particularly enjoyed this because it gave us all the flexibility to hike at our own pace, chat, be solo, think, push ourselves, or soak it all in. Listening to the sound of ice crunch beneath your feet whilst staring out into miles of glaciers is a unique meditation.

Every campsite came with its own quirks and elegances. Some were better for sleeping, and others were better for staying awake… Maybe the donkeys balking or the rocks beneath the tent shaped you into a banana. Either way, every camp had its own test for you.

Despite the havoc playing in the crew’s stomachs, we managed to keep our ‘collective battery’ adequately charged. Nutella was a sought-after commodity; the soup was like a lover that kept our souls warm. Luxuries present themselves in curious ways. Some give you life; others provide you with peace of mind.

Taking on an adventure of this nature comes with an inherent and accepted set of risks. It goes without saying that death is a potential possibility in the Karakoram. The chance of it happening to those around you is not to be laughed at.

You think of death often out in the Karakoram. It whispers in your ear and rings a bell to let you know it’s nearby. You hope it doesn’t come to greet anyone on your team, and you do everything possible to mitigate the chances of it happening to you. In a humbling way, it demands a presence from you that you may not find in the city. Every step is selected with an ounce more care, and decisions are thought over thrice.

At two of our campsites, we witnessed the misfortunes of an expedition gone wrong. We entered a beautiful campsite to find a lady seeking help for a team member that had fallen ill. From what we were told, we understood that he had been sick for three to four days and was struggling to breathe. He was at the camp ahead of us without the health and strength to hike down to lower altitudes.

His team was apparently inadequately prepared and lacked the equipment to call for help in an emergency. In highly isolated environments like the Karakoram, it should be an absolute necessity for team leaders and members to carry or have access to a satellite phone and Garmin in-reach (Or something similar, we had a Garmin In Reach).

Our team leader presented like an angel with a satellite phone and Garmin for the lady to use. The two of them worked together to call for help, but other circumstances revealed themselves and proceeded to increase the severity of the situation. Unfortunately, the team member of the other expedition that had fallen ill did not take out Global Rescue helicopter insurance. Heading out to Snow Lake with helicopter insurance was a non-negotiable.

The following day came around, and the team gathered as we usually would eat breakfast. Cups filled with two-to-three black tea bags, chapatis slathered with Nutella, and thick slices of balti bread were the usual culprits. The lady from the other team burst into our tent, exclaiming a short statement repeatedly in French. Those who understood French immediately looked shocked. The translation and silence quickly followed. The man from the other team had died overnight. A group of porters attempted to carry him off the glacier and down to lower camps, but he did not make it.

It was a sad way to start the day. I started at the back of the pack and walked solemnly with my thoughts and aggravated stomach. I did not know the man, but I couldn’t help but think about his family and friends back home. It made me think of my own family and how I would feel if that were to be my own Father or Mother.

Life is delicate and fickle. In the high moments or when life feels easy, it’s easy to forget the delicateness of life. When life is busy back in our lives outside of the mountains, we tend to forget about the precious nature of our existence.

Things go well till they don’t, and situations turn on a dime in seconds, hours, or days. In the upcoming days, we walked past the man’s body and sent the coordinates to those who needed them.

The experience didn’t mean that our adventure was unsafe or risky, and it simply highlighted how things can change quickly. We made it to the next campsite after a short day of hiking (I arrived covered in mud) and settled into 36 hours of rest.

Funnily enough, the shortest day of hiking would end up being my most challenging day due to the case of acute gastritis I was dealing with. In conversations with a friend on the trip, we decided that our first rest day was instrumental in bonding with the group. We played charades and cards for hours on end. The laughs we shared formed a glue between us that would solidify us as a team for the days ahead. I still laugh remembering these moments now.

We were the only team left on the Askole side of the glacier attempting a pass of Snow Lake. The weather still didn’t look favorable, and clouds hung low. Our next campsite was memorable for a variety of reasons.

We aptly named it “Rock-nation”. The type of rocks that will cause an ankle injury if you lapse concentration even for a second. Tents were angled at weird angles and in opportunistic places. Our mess tent was cramped, but at the same time, it felt cozy. We made the most of the rocks we had been given and furnished the space with bags of chapati flour.

The chapati bags made great lounges. In the evenings, as the generator hummed and the sounds of our shell jackets ruffled, I enjoyed the simplicity of living. Some of us exchanged music that we had saved offline and hoped the upcoming weather would provide an opportunity.

Days passed at rock-nation, and each day, the odds of making an attempt at Snow Lake seemed to diminish. Our group remained remarkably optimistic, but deep within us, we all understood the reality of the situation.

The probability of returning was high. In July, 28 teams attempted to make a pass of Snow Lake, and none were successful. We heard reasons around ‘weather’, porters, and crevasses. In the beginning, I didn’t really understand any of these reasons. In my mind, you could trek through snow or rain. We had a strong team of porters, so that seemed no issue. And crevasses… well, how wide could they be? Through my rose-tinted mountaineering glasses, my opportunistic self believed that we would make it across the pass.

I found out that ‘weather’ usually refers to visibility. If the lead guide cannot see a clear path through crevasse fields, glaciers, and snow passes, it is understandable how the weather is a valid reason to return home.

Similar to the big mountains, summit pushes rely heavily on weather windows. If you don’t have a good weather window, it doesn’t matter how skilled or determined you are — you cannot go. Secondly, the weather conditions can also make things very difficult for the porters. They do not have high-quality, expensive gear like the clients. Most of them are in $2 plastic shoes and do not have down jackets or protective shells.

Some don’t have sunglasses, and they most certainly don’t own harnesses. An expedition like a snow lake is impossible without the porters, and their lives should be put at risk in no circumstances. If the porters believe that it is unsafe to make a crossing, the group cannot continue. As for the crevasses… they had increased in size and number, but we were determined to find a way around them and through them.

At the start of our 21-day expedition, Chris had factored in an allotment of contingency days. These days were scheduled in case we missed flights, team members got sick, recovered, and for bad weather. We had run out of contingency days. It was time to decide whether to head for the pass or home. To our surprise, the low-lying clouds had lifted, and the rain had paused. Back down the glacier, there were glimpses of sunlight and hopeful openings of blue skies. It was now or never. We had been allowed to press forward.

We assembled our packed lunches, microspikes, and 6000m boots. It was time to make a charge for Snow Lake. Visibility on the horizon was still low, but we had enough to work through the maze of crevasses. For the first time, we put our harnesses on and roped up. Fourteen of us were tied together with about two meters of rope between each person.

Roping up meant that we mitigated the risk of falling into crevasses. If someone was to fall, the person behind and in front of them would hold tension on the rope so they wouldn’t fall into the dark abysses below. Sure enough, this system worked exactly how it was meant to. At some stage throughout the day, five to six people fell into holes or small crevasse openings. These holes were often covered by loose snow that would give way when stepped on. The porters roped up in teams and made their way across the crevasse field. It was a spectacle to witness these ‘trains’ of humans navigating across mind-blowing snowy vistas.

After many hours of weaving, we made it into heavier snow. We trudged through snow and avoided bigger and bigger crevasses. There were new worlds below our feet, ones I didn’t wish to explore. Swift-moving porters made it to and set up the Snow Lake base camp before our team did. We could see the tents in the distance and slowly worked our way toward them.

My overarching highlight of the trip was making it to the Snow Lake base camp. The team marched in and untied us from the rope, which kept us secure and safe. We walked into our first ‘snow camp’. Our mess tent was staged upon a small patch of snow, and 14 chairs awaited us.

As we sat down, smiles beamed and bounced around in all directions. Endorphins overflowed, and a sense of achievement was within us. We cheered, we laughed, and we celebrated. More significant days awaited us, however, making it to Snow Lake Base Camp signified the point of no return. We were going to be the first team to make a crossing of Snow Lake glaciers. Celebrations came in the form of oversized bowls of popcorn and Nutella-filled altitude-style birthday cakes. One of the team members, Clark, celebrated his birthday on the day we made it to Snow Lake Base Camp. A birthday I’m sure he’ll never forget.

We cheered for our chef Ali as if we were at a soccer stadium and put on every warm piece of clothing we owned. Some of us went on to spend hours in the kitchen tent. It was our version of a steam room. Porters repeatedly bought bowls of snow to be melted and transformed into tea and soup.

In life, we may only get to experience many things once. Objectively, every moment in its uniqueness only presents once. However, for experiences like adventures, you may only ever do a particular style of adventure 10–20 times throughout your life. Even this is not guaranteed. It’s a concept I think about often. If you were to group specific experiences, observe the frequency at which you do them, and then multiply them by 40 (which sounds like a reasonable number), you would come up with a number that may be loosely representative of how many times you will do this in your life.

Life happens, families start, the climate of the world shifts, finances waiver, jobs tie you down, and all of a sudden, this number can be easily halved. It’s funny to highlight how very few times we do many things. We think we will come back to see things again, but often we don’t.

Above all, this notion highlights the importance of making the most of the moment while in it. This paragraph is simply a tangential idea to the Snow Lake narrative. Yet, I know there will only be limited times in my life I spend nestled in a kitchen tent drinking tea at the base of a glacier with a bunch of strangers turned close friends. I hope as you read this, you find yourself grateful for the set of experiences you had and shared today.

Four-thirty comes around. Surprisingly, I slept well. My body has adapted to altitude after 5 weeks and 1.5 expeditions in the Karakoram. I went to bed with everything I wore the day before. I didn’t even take my harness off. I took the lining out of my 6000m boots and shoved it in the bottom of my sleeping bag to dry the sweat and prepare them for another day of snow stomping. Snow weighs heavily on my tent’s roof, forming a small wall around the base.

Once again, a place I never dreamed of sleeping. I’m up and packed early, as requested by Chris. The porters are slow to get up, and I don’t blame them. As the sleepy camp came to life, I returned to the warm confines of the kitchen tent. Before 6 am on a Sunday morning, I’m sipping tea, watching the kitchen team work in harmony, filming snowfall, and sharing life stories with one of the team members on the trip. It’s like a movie. I think of the running I’d typically be doing on a Sunday morning, and at this moment, I wouldn’t change a thing. I hope time slows down for me.

I want to stay wrapped up with my tea for a bit longer. The day ahead will be our most challenging day yet, and I’m ready for it, but I’m in no rush to start.

We’ve roped up again. I can feel the seriousness in the air. The porter army sings. I hope it echoed in the souls of those in lands far away. We all wish for a safe crossing and a successful pass. Deep snow stares us all in the face, asking who will make the first footprints.

Our lead guide Sohail led the way, breaking trail in the knee-deep snow. Trail-breaking is physically demanding and mentally draining. You fall a little deeper than those at the back of the line. Every step comes with a degree of uncertainty. Not to mention the pressure that comes with picking a safe route. Sohail was our superhero. Over the next 12 hours, he would lead the way.

Step by step, we made our way up toward the plateau at the top of the pass. Looking back behind us, trains of porters followed in our footsteps. We hoped that our trail-breaking would make it easier for them to follow. The weather wasn’t ideal as visibility was poor. The higher we ventured onto the pass, the worse it became. Hours passed with very little distance gained.

As we reached the top of the pass, we became engulfed in a ‘whiteout. Snow was angling at our eyes, and visibility was reduced. To zero. No longer could we make out the horizon line, crevasses, or the ridge lines of surrounding mountains. Sohail continued on his bearing and slowly led us across the pass. The porters sometimes deviated off our path, which seemed illogical and unsafe. We soon returned to the same path and onto the other side of Snow Lake Pass.

We had made it across the pass! We were also far from where we wanted to be. Fortune favors the brave, and on the day of our crossing, fortune comes in the form of footsteps. Another team was also making an attempt at Snow Lake from the other side of the glacier. This meant that we could join up with the path that they made and that they could join ours. The crevasses became more frequent and more dangerous on the other side. A way to follow was a true blessing from the mountain gods.

The crossing was our most challenging day as a team. For those that didn’t have 6000m boots, their feet were freezing as the ice melted into their shoes. Each step was a small battle, and being tied up required coordination and patience. We all slipped and fell many times, which, as you can imagine, makes any kind of efficiency near impossible.

Those at the back felt like they were being pulled by the front and vice-versa for those at the front. Late in the afternoon, we made it to the base of the pass. We were presented with an option to sleep another night in the snow or push forward to a better campsite. With tired legs, we collectively decided to make a charge for the next camp. Running on little energy, we walked quietly and wearily to the camp. My boots had given me blisters, but I still had nothing to complain about.

Coming into camp, I took my boots off to air out my blisters. This was a critical error. The ground was icy, and the rain had set in. My bags had not arrived, and my socks were yet. This decision brought on a chill that would make me cold for the next few hours. Revival came from the kitchen tent in the liquid form of honey, lemon and sugar tea. An elixir is worth more than gold.

The camp was drowned by rain, and the team ate together for the first time in the kitchen tent. Another memorable moment was when we crowded into the kitchen tent to share dinner. We had successfully made it across the pass, and it was now time to breathe a sigh of relief. The hardest part was complete.

The days that followed would take us to many more beautiful campsites. We spent hours walking along and across more glaciers. This time, things were different. We walked across the glaciers with reinvigorated energy knowing that every step brought about a new landscape. The days were long as we made up for the lost time. Initially, there were meant to be shorter days after the crossing, but we had to combine days to make it ‘home’ on time. Each day breathing became more manageable as we dropped in altitude. The trekking was smoother, and the kilometers passed faster.

As the final days were upon us, we all soaked up the time offline amongst some of the world’s most picturesque mountains. We had been and were still truly deep in the wild.

From above, our camp looked like a colorful painting. Brightly colored tents speckled the campsites we temporarily inhabited. We transformed the camps into small shanty towns when the sun came out. Clothes were draped over every rock that faced the sun, and makeshift lines were constructed to hang our clothes.

We let out feet recover in glacial streams and enjoyed our final soups. In the later days, we were out of goat but never out of chapati. Every day, we shared our highs and our lows. Reoccurring gratitude the team held was for the collective belief and positivity the group maintained throughout the mission. For the most part, lows never carried too much weight because they were quickly translated into lessons or laughs.

The final day arrived. In the mess tent, Jackson played against my competitive nature. Knowing my inner competitor, I was challenged to keep up with one of our team members, Brogan. Brogan is an efficient mover and hikes at a fast pace. Known to challenge the lead porters, Brogan will hold pace all day.

Brogan and I set off in the early hours as the sun rose and set off at a solid pace in the cool morning shadows. We had a blast hiking fast and taking on porters. At the time, we would break into a jog as the porters picked up the pace. The only difference is that they were carrying 30kg, and we were packing 12kg. On our final day, we covered 21km, which rounded out around 130km for the entire mission. It was a stunning end to a beautifully eventful passing of Snow Lake.

The rest of this day would be an entirely new adventure in itself. In summary, we built roads, went on the most dangerous motorbike ride of our lives, and crossed bridges being built as we walked across.

As I picked up my stained tea mug and taped together my ripped sleeping bag on the last day or put on the same t-shirt for the 15th day in a row, it was overwhelmingly clear to me that this adventure was perfect. We did not have bluebird skies every day, but we had enough visibility when we needed it.

Before leaving Australia, a friend said, “Abundance is having enough to do what you want, at the time you want to do it.” This resonated with me on the Snow Lake tour. Flights flew when we needed them to, just as the jeeps transported us to villages when the odds were against us.

Our team remained healthy, and sickness never became overbearing. Our positivity was formidable, and the porters believed in the mission as much as we did. We will remember the achievement of our adventure for the rest of our lives, but I will remember the relationships and memories we made even more. To the snowflake that falls on the mud-covered jagged rock, thank you. Perfection needs a place to land; over these weeks, it landed on Snow Lake.

Thank you once again to Chris from Epic Expeditions, Jackson Groves and Sohail Sahki for leading us on this wild adventure.

Thank you to Brogan, Clark, Dean, Ilayda, Kat, Noemi, Scott, Vasco, and Yagmur for all the smiles, conversations, laughter and memories.

Here is a collection of a few more of Josh’s photos from the trek: